Direct communication is impossible

It's more about who you are than what you say.

Bill was one of my favorite public people from the early 2000s. He was an incredible writer, a rousing speaker, and when he was at his peak, he had a major impact on the sociopolitical scene of the time.

When asked how he managed to be such an effective communicator, Bill said the secret was this:

Know what you’re talking talking about.

Love what you’re talking about.

Believe in what you’re talking about.

That’s it.

For a long time, I thought this was true, and modeled my own communication style after Bill’s, with some amount of success.

I started telling people about Bill’s method, saying, here’s all you gotta do to reach people. But it didn’t always work.

When I first joined Twitter (now called X) years ago, I met with some strong resistance to my arguments from atheists and even other Christians. A lot of it was incoherent, so I wrote it off as nothing to worry about. At the same time, I was becoming increasingly frustrated in my social circle as I watched my friends get into arguments and even leave the group over what I saw as relatively minor disagreements.

A friend pulled all this together when he told me that direct communication is impossible, no matter how sincere people are. He reminded me of that every time I had a frustrating encounter with a critic. He said it again when I expressed dismay over the misunderstandings that were happening in our social circle.

I realized my friend might be right, and it bothered me. The social aspect I didn’t worry about much at the time, but as someone who lectures for a living and is active in ministry, I was worried about my ability to communicate. I thought I had the secret sauce—Bill’s formula—but maybe that wasn’t enough.

I then realized that Bill, as great as he was at communicating, only managed to galvanize the people who were already on board, or willing to come on board, with what he was saying. I don’t think he managed to convert many people who were on the other side. Which is okay. It’s good to encourage and unify the people already in your group. But what if you want to persuade people who aren’t?

Experts in the art of persuasion, like Dilbert comics creator, Scott Adams, talk about persuasion techniques, like “pacing and leading,” using visuals and contrasts, and even hypnosis, to make your case. But these are tactics, not strategies. Before you can be tactical, you need to be strategic. A lot of communication comes down to two general ways in which most people are persuaded: pathos (emotion) and logos (reason). The strategy is knowing when to use which, and on whom.

Thousands of years ago, it was the philosopher, Aristotle, who pointed out pretty significant differences between people when it comes to communication style. He identified two broad groups:

Rhetorical: people who are mostly swayed by pathos or appeals to emotion.

Dialectical: people who are mostly swayed by logos or appeals to reason.

These two groups of people face challenges when trying to communicate with each other. My own experience has borne this out many times.

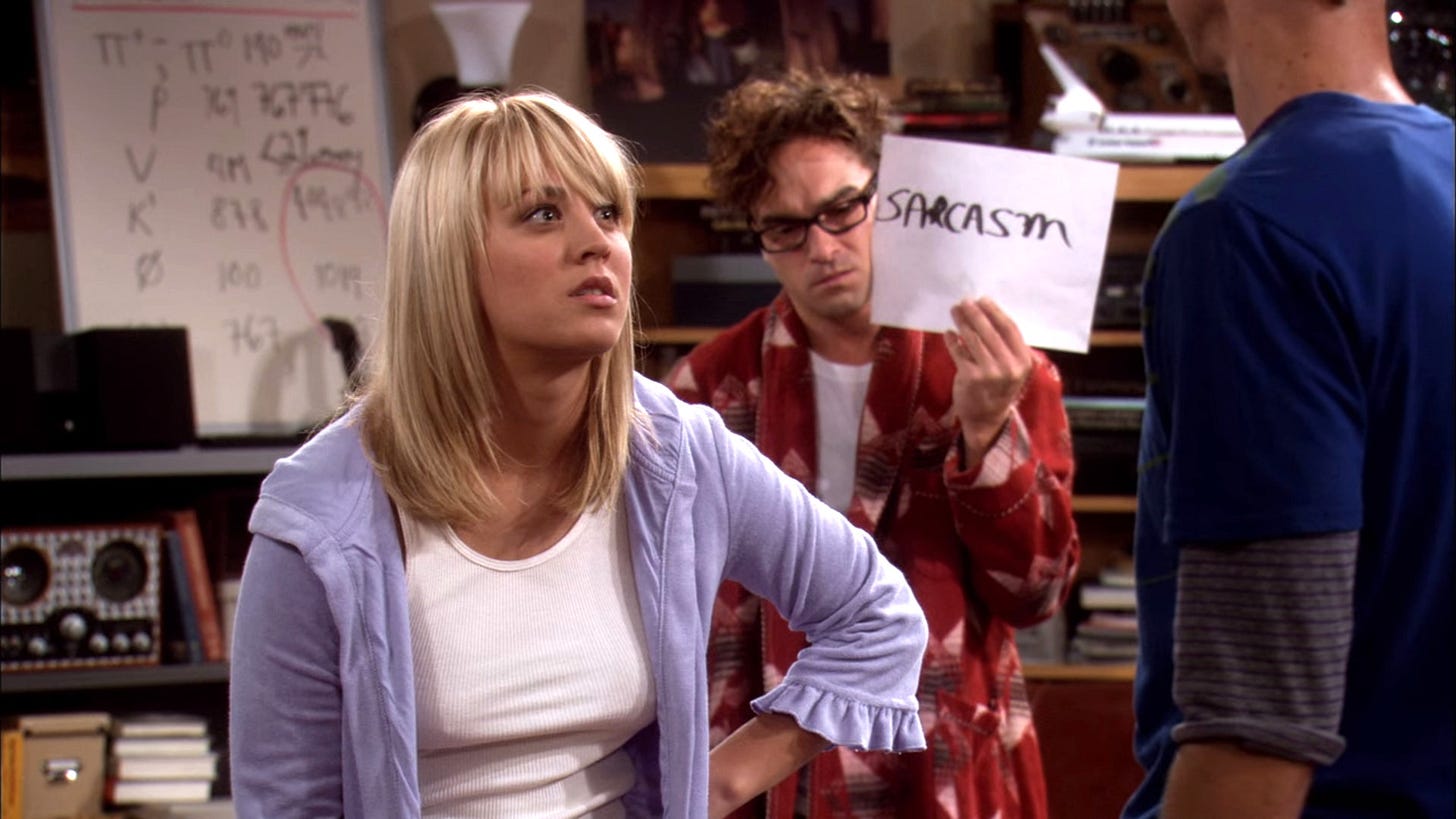

I am more dialectical. So much so that my husband started calling me Sheldona, after Sheldon Cooper from The Big Bang Theory. Sheldon and I are more often persuaded by dialectic, and we both struggle to understand a lot of rhetoric, including sarcasm.

When trying to understand someone's position, or to make my position known, I do what dialectical people do: make direct statements and ask sincere questions. I don’t quite go as far as Sheldon, who once tried to persuade Penny to let him take her place on a trip to Switzerland by forcing her to watch a PowerPoint presentation. But, like Sheldon, I sometimes fail despite my best efforts.

It took a lot of frustrating encounters to realize that for rhetorical people, a lot of communication is implied, not directly stated.

Specifically, I discovered that:

Making factual statements can be the equivalent of “shoulding” people. I recently stated on social media that if you want to know what bothers someone, observe how they criticize you. That’s it. Just a statement. But a commenter thought I was implying that you therefore shouldn’t criticize people, which was not at all my point. It led to a lot of confusion.

Asking a question can be the equivalent of making a statement. Let’s say you and a friend are out for an afternoon, and you encounter an activist who’s asking for signatures on a petition. Your friend signs it, but for whatever reason you decide not to. Dismayed, your friend says, “You're not signing it? Do you want these people to suffer?” This isn't a request for information. It’s a statement. The meaning is, “I’m upset you’re not supporting something I care about. I want you to reconsider.” They think everyone communicates this way, and often look for the implied meaning of questions, even when there isn’t any.

This is why rhetorical people get frustrated when they encounter someone like me or Sheldon. That direct style can be so confusing to them, that they actually think we’re being disingenuous or manipulative.

Hence, direct communication is impossible.

At least for anyone other than two dialectical people. And—let’s be real—even dialectical people get emotional.

So, what do we do, give up on trying to communicate with anyone other than people exactly like ourselves?

Of course not.

For those of us who communicate for a living, maybe we need to rethink how to reach people who are not like us. And here’s the good news. Or possibly bad news, depending on how you look at it. Aristotle identified a third way to communicate, after pathos and logos: ethos, or character. So powerful is character that Aristotle claimed it may be the most effective means of persuasion out of all of them.1

How persuasive is character? Consider this. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Christians more often point to who Jesus is and what He did than to what He said when trying to convince others how much He loves them.

If you want to be a good communicator, I still recommend Bill’s formula. I don’t think you can be a good communicator without it, and even science backs that up. Scott Adams’ various techniques (which are mostly rhetorical) are also helpful. But that’s not enough. If you lack the skill to be dialectical when you’re rhetorical, or rhetorical when you’re dialectical, work on the most powerful persuasive strategy there is: your character.

Rhetoric, p.26, Aeterna Press

"It's more about who you are than what you say." Isn't that the truth? Look at the politicians who spew party rhetoric instead of saying what they believe & know to be the truth. So easy to tell who is genuine (who they are) and who isn't. Public speakers who don't use notes/cards/teleprompters are much for effective than those who do.